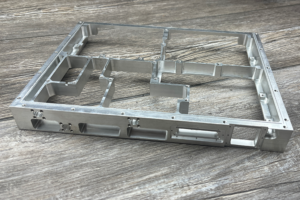

Most CNC-machined parts are designed to mate with something else: another component, a housing, a bearing, a pin, or a shaft. When that fit is right, assemblies go together smoothly and perform as expected. But when it’s wrong, the result is often binding, vibration, leaks, or premature wear.

Most CNC-machined parts are designed to mate with something else: another component, a housing, a bearing, a pin, or a shaft. When that fit is right, assemblies go together smoothly and perform as expected. But when it’s wrong, the result is often binding, vibration, leaks, or premature wear.

In many cases, the root cause is missing information rather than a single “bad” dimension. Either the tolerances weren’t defined clearly enough, the intended fit wasn’t specified, or the finish and assembly conditions weren’t accounted for. In precision CNC machining, that’s how a fit that looks right in CAD can turn into an assembly problem on the shop floor.

Avoiding those problems starts with clear fit specifications and an understanding of what can change between machining and final assembly.

Table of Contents

Fit Types at a Glance

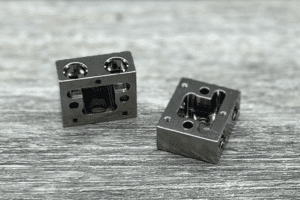

Fits describe how two mating parts (typically a shaft and a hole) relate to each other based on their tolerances.

A clearance fit means the hole is always slightly larger than the shaft, allowing movement, rotation, or easy disassembly. This fit is common when parts need to slide, adjust, or be removed without tools.

An interference fit is the opposite. The shaft is intentionally larger than the hole, creating a locked connection that typically requires pressing, heating, or cooling to assemble. This approach is common for permanent or load-bearing assemblies where movement has to be eliminated.

A transition fit falls between the two. Depending on where each part lands within its tolerance range, the final assembly may end up with a slight gap or slight interference. It’s often chosen when you need precise alignment and a snug connection, but not a full press fit.

The key is to specify the fit you need, then ensure your tolerances support it.

Where Designs Go Wrong

Even when engineers understand fit types, the details don’t always make it onto the drawing. Two issues come up more than any others, and both can turn a straightforward fit into an expensive problem:

- Nominal dimensions without tolerances. The number on the drawing might look correct, but without knowing how precise that dimension needs to be, the shop is left guessing. A hole marked as 0.500" could mean ±0.010" for a loose fit or ±0.001" for a press fit. If the drawing doesn’t say, there’s no way to know which one you intended.

- Functional intent not fully documented. Engineers usually know exactly what a part is fitting into and how tight that connection needs to be, but the shop can’t infer that intent unless it’s documented.

When these details are missing, the result is usually a phone call to clarify, a delayed timeline, or a part that needs rework after the fact. The more clearly the fits are defined up front, the more predictable the cost and lead time tend to be.

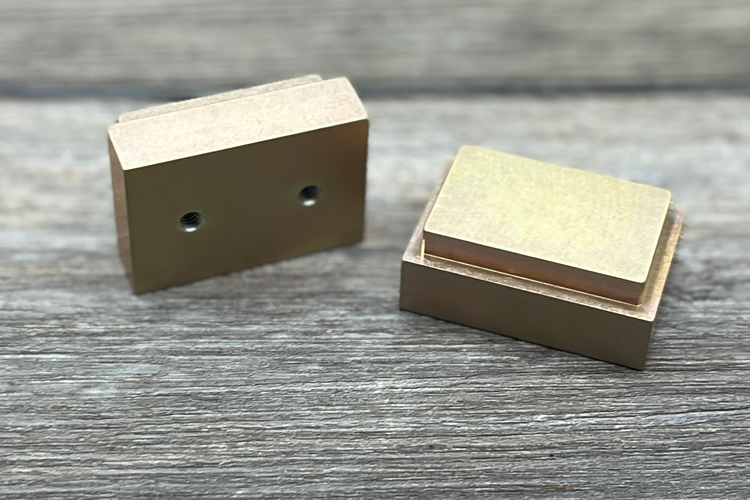

The Coating Factor

Secondary processes like anodizing, plating, and powder coating add measurable thickness to part surfaces. That thickness builds on both sides of a feature, which means a clearance fit designed in CAD can become an interference fit after finishing.

Coating-related fit problems are among the most common we see, and they usually come down to assuming machined dimensions will still be correct after finishing. If tolerances aren’t adjusted for coating buildup, parts that measure correctly after machining won’t assemble correctly afterward.

| Process | Typical thickness (per side) | What’s often missed |

|---|---|---|

| Anodizing (Type II) | 0.0004"–0.001" | Partial penetration, but the surface still grows enough to affect fit |

| Hardcoat Anodizing (Type III) | 0.001"–0.003" | Can grow unevenly on complex geometries |

| Zinc Plating | 0.0002"–0.0005" | Internal diameters shrink by twice the thickness |

| Nickel Plating | 0.0005"–0.0015" | A harder surface can gall during assembly without lubrication |

| Powder Coating | 0.002"–0.008" | Much thicker than paint; holes often need masking |

Heat treating doesn't add thickness, but it can distort features enough to shift parts out of tolerance. In some cases, final machining may be required after treatment.

Define the Intent First

The most reliable way to avoid fit-related problems is to start with what the mating feature actually needs to do. Before assigning a dimension or tolerance, get clear on how the part needs to behave once assembled. Does it need to slide freely, locate precisely, carry a load, or lock in place? When that intent is clear, the right fit type and tolerance range usually follow naturally.

This approach also makes it easier to account for real-world variables. When those details are considered up front, fits are more predictable, assemblies go together as intended, and late-stage surprises are far less likely.

At Approved Machining, we see the best outcomes when fit intent is clearly documented and discussed early. Clear communication helps reduce rework, manage lead times, and ensure parts perform as designed in the final assembly.

If you’re not sure whether your fit specifications are fully defined, or if you want input before production, our precision CNC machine shop would be happy to help. Contact Approved Machining to talk through your next project.